The condition of being under the watchful eye of the camera at all times is perhaps a defining experience of the 21st century. If, in 1967, the Parisian theorist Guy Debord opined that we live in “the society of the spectacle,” by now, we seem to have upped the ante, as we witness the blurring of spectacle into surveillance. This is the conceit behind Paul Pfeiffer’s provocative midcareer retrospective at MOCA entitled “Prologue to the Story of the Birth of Freedom.” The show dramatizes the sensations of seeing and being seen.

The earliest work in the show lays out some stakes. In The Pure Products Go Crazy (1998), clips of Tom Cruise appropriated from Risky Business (1983) have the actor writhing on a couch in a continuous loop. Viewers become voyeurs of a bizarre suburban ritual. But Pfeiffer projects the scene on the wall at such close range that the image is mere inches in size, as if protecting Cruise or refusing to lull and seduce viewers. It’s an example of how the artist deftly manipulates scale, often to create a sense of dissonance.

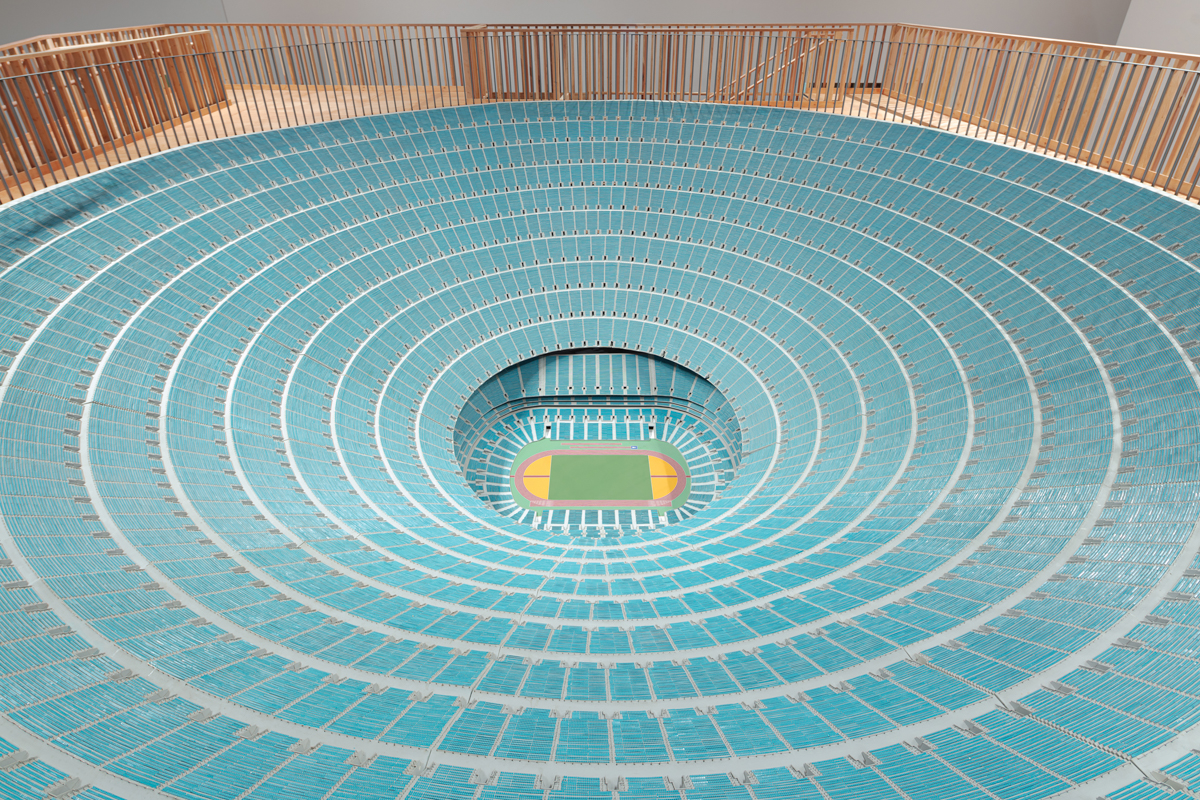

Pfeiffer’s scale shifting recurs in Vitruvian Figure (2008), in which we see a 26-foot-wide model inspired by the 2000 Olympic Stadium in Sydney, the largest ever built, with 100,000 seats. The artist’s version seats a whopping one million spectators; it boggles the mind to imagine so many people attending a sporting event. Here, though, he turns the viewing apparatus into the object of the gaze: visitors approach the model from a winding ramp, then view the empty stadium from above, taking in the million seats he painstakingly constructed.

Starting in 2000, spectacle sports became one of the artist’s primary preoccupations. Several of Pfeiffer’s pieces in the exhibition isolate sports photographs and abstract them from their original context.“Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse” (2000–ongoing) is a series of large C-prints of found photographs from which the artist digitally removes details like jersey numbers and stadium advertisements. In one image, a lone basketball player is captured mid-jump above a well-lit court, arms outstretched above him. Instead of a bold “23” or “30,” the athlete wears a plain white jersey. In the background, fans pack nearly eerie unmarked bleachers. A spotlight shines brightly in the distance, toward the camera, silhouetting the player. With this gesture, Pfeiffer emphasizes the figures in the photos, making them transcendent, as if revealing our culture’s new religion: athleticism and advertisements.

Elsewhere, instead of glorifying the players, he erases them.In each of the films comprising the trilogy The Long Count (2000–2001), the camera pans through a boxing ring. But there are no boxers, just a hyped-up crowd. The videos are taken from televised matches that Muhammad Ali fought against Sonny Liston (1964), George Foreman (1974), and Joe Frazier (1975). These iconic bouts were, even in those early days of television, watched by millions of viewers across the globe. In the videos, the boxing rings quiver with movement but reveal no fights. Pfeiffer edited footage of the empty rings, repeating segments on a loop so that each video runs for the duration of a match. There are no victories, no celebrations of champions—only the looping movement of the camera panning across each ring. Pfeiffer’s selective editing captures the setting, but erases the content it’s designed to house. Instead, we are left to ruminate on the environment, infrastructure, and audience. We witness the awe and anticipation of the mostly white observers who were presumably wealthy enough to afford the pricey tickets, only to watch Black and brown athletes entertain them, and the culture at large.

Pfeiffer reveals the many different systems by which spectacles are made, and chief among these, of course, are television and film. Self-Portrait as a Fountain (2000), a nod to the well-known murder scene in Hitchcock’s Psycho, features a showerhead that continuously rains water into a bathtub. Meanwhile, six closed-circuit surveillance cameras are trained on the shower, mimicking the myriad angles used in the film’s iconic shower scene. And in Cross Hall (2008), a projector displays a livestream of a handsomely situated podium, as if awaiting a state official’s television address. But in the middle of the projection, a peep hole has been drilled into the wall, revealing behind it a darkened room and an open doorway. The camera, situated beyond the visible scene, is pointed at a diorama, streaming, it turns out, a podium in miniature. The work highlights the manipulability of media, and shows how some things are broadcast for all to see—often in the guise of transparency—and yet often, all this noise is really meant to distract from what goes on behind closed doors.

Throughout, celebrity culture meets surveillance, as it does in 24 Landscapes (2000/2008), a display culled from photographs of Marilyn Monroe at Santa Monica Beach, shot by George Barris in 1962, shortly before her untimely death. Having carefully edited Monroe out of the images, what Pfeiffer offers instead is a neutralized environment, an often-soft-focus gaze at the seashore, and an awareness of the tragedy that was soon to come. For Incarnator (2018–ongoing), Pfeiffer hired Philippine saint carvers, encarnadores, to render Justin Bieber in wood as a Christ-like idol. They meticulously carved a likeness, tattoos and all, then cut the sculpture into pieces that Pfeiffer has elsewhere shown assembled to form the whole, but here displays separately. Still, the pop star’s features remain recognizable. We are made to feel that we are in the presence of someone or something otherworldly, yet someone we have dismembered and greedily consumed. Perhaps, for a moment, we are who we are when no one is watching.